You let the first half of your thesis timeline slip by, you’re buried in literature, ChatGPT keeps spitting out nonsense, and your supervisor has basically given up on you? It’s time for some real thesis tips that actually help.

That’s exactly why this post gives you seven tips for your Bachelor’s thesis that no one else will tell you – but that can actually help you reduce the pressure and finally feel like: “Okay, I’ve got this.”

1. Your Bachelor’s Thesis Is Just a Training Exercise

The biggest misconception students have is believing their Bachelor’s thesis needs to be a groundbreaking scientific contribution. Maybe it’s the term “academic thesis,” or maybe it’s just the unrealistic expectations we place on ourselves.

But here’s the truth: your thesis is, first and foremost, proof that you’re capable of doing academic work. Nothing more, but also nothing less.

What does that actually mean?

- You need to show that you can develop a meaningful research question.

- You need to research, analyze, and correctly cite relevant literature.

- You need to apply a method in a clear, comprehensible way to answer your question.

What you don’t need to do:

- Develop new theories

- Open up an entirely new field of research

- Or produce world-changing insights

Once you let go of the idea that your thesis has to be perfect, things get a whole lot easier. The goal isn’t to reinvent the wheel, but to work cleanly and transparently.

Pro tip: Write this sentence on a sticky note and slap it on your laptop screen: “Good is good enough.”

2. Your Research Question Is the Key

A lot of people think the topic is the most important thing. They spend weeks hunting for the perfect one.

“I want to do something with social media… or maybe sustainability?”

But let’s be honest: the topic alone won’t get you far. What really matters is the question you ask.

It’s the clearly defined question that turns a general topic into an actual research project. It gives your thesis direction, narrows the scope, and determines what literature you need and which method you should use. If you linger too long on a vague topic, you’ll lose your thread and start thinking in all directions at once—without making any progress.

Example: “Loneliness in remote work” – sure, that’s a topic. But what exactly is it about?

If you ask: “How does working from home affect the sense of belonging among entry-level employees in service agencies?” – then you suddenly have a clear direction. Something you can actually study.

So it’s really worth putting in extra care at this stage. If you can clearly and precisely formulate your question, everything else will become a lot easier. And your research question can be more niche than you might think – as long as it’s important to a specific target group.

3. Your Supervisor Is Not Your Personal Coach

Many students expect supervision to involve regular meetings, constructive feedback, and guidance during difficult phases. The reality? Usually… far less ideal.

Supervisors are usually extremely busy. They’re working on their own research, teaching classes, writing grant proposals – and supervising ten other theses besides yours. That doesn’t mean they don’t want to help. But they often just don’t have the capacity to walk you through every step.

That’s why one of the most underrated thesis tips is this: don’t wait around for help and manage the relationship actively.

Ask specific questions, be well-prepared, and provide clear interim results when needed. Instead of saying “I’m unsure about my outline,” say something like: “I’m considering combining chapters 2 and 3 – what’s your take on that?” These types of questions are easier to answer and increase the chances of getting genuinely helpful feedback.

The better you communicate, the more likely you are to get useful responses.

You need to act as the project manager of your own thesis. And that means: making your own decisions.

4. Writer’s Block Has Causes

Hardly anyone just breezes through their Bachelor’s thesis. Most people hit a phase where nothing works anymore. You open your document, stare at the screen, and have no clue how to even begin. But these blocks have causes – and they can be deciphered.

It’s usually not laziness or a lack of motivation – it’s uncertainty. You don’t know exactly what to write. Or you’re afraid of getting something wrong. Or maybe you’re just overwhelmed by the amount of information.

So what helps? Just start writing with no pressure.

Type out your thoughts, even if they’re still rough. Or start by jotting down a few bullet points outlining the general direction. The main thing is: get something written. Use an AI tool to get feedback – ChatGPT won’t judge you!

Be patient with yourself and remember: writing helps you think. Not everything needs to be perfect from the beginning. A lot of clarity comes only once things are on the page.

5. Rhythm Over Rigid Plans

The most carefully crafted weekly schedule is pointless if it doesn’t fit into your actual life. Many students plan based on an ideal version of themselves: they assume they’ll be equally productive every day, that motivation will always be available on demand, and that the writing process will unfold in a straight line. But reality is different. Some days you’re in the flow – and some days, you’re not. And that’s totally fine.

One of the most practical thesis tips is this: good time management doesn’t mean scheduling every hour of your day. It means creating realistic time slots when you can work – and building in space for setbacks and breaks. A writing day where you only get one page done can be just as valuable as one where you restructure two chapters or sort through literature.

Grab the books Deep Work and The One Thing – or just a summary. That’s really all you need.

6. The Biggest Time Trap? Literature

You want to start your research – and suddenly you’ve found 50 articles, 20 of which sound super relevant, and each one references 10 more. Welcome to the literature jungle.

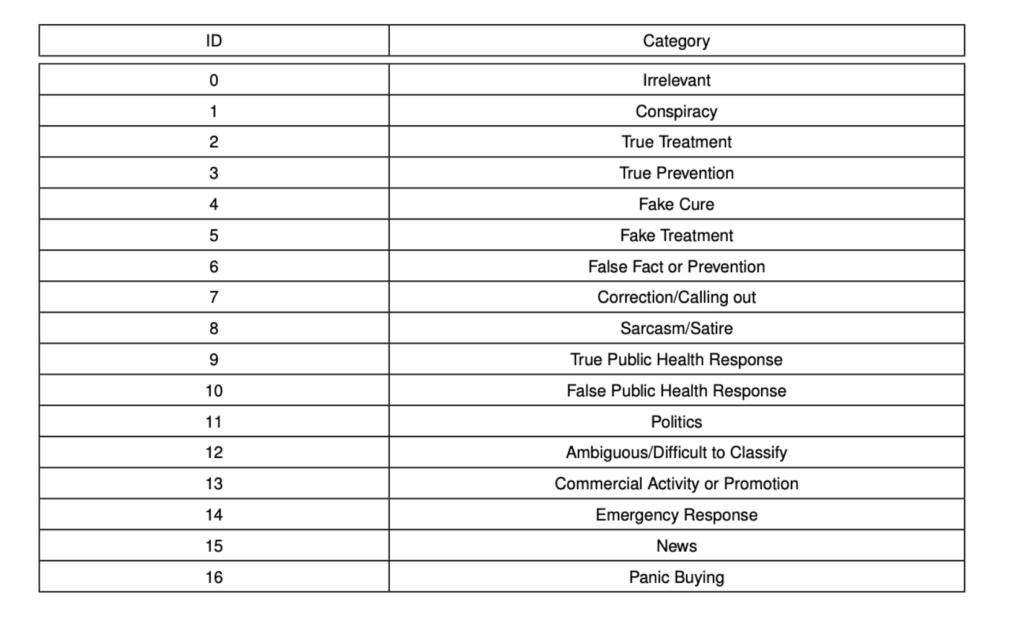

What many underestimate: It’s not the writing that eats up your time – it’s the endless searching, reading, and sorting. Eventually, you lose track of everything. AI tools won’t help either – they can’t tell a Organization Science article from some dodgy MDPI fluff piece.

The trick isn’t to read everything – it’s knowing what you don’t need to read. A solid research question helps enormously because it automatically narrows down your literature. You only need to read what brings you closer to answering your research question and what’s valued in your academic field. If not – toss it out, even if it’s thematically related.

A reference management program can also help you keep track and insert citations correctly – without spending hours formatting.

7. The Discussion Is Not a Summary

If you’ve made it to the discussion section, you’ve already come a long way. And yet – this is often the hardest part of the whole thesis. Because now it’s no longer just about presenting results. Now you have to interpret and critically reflect on them.

The discussion is where you show that you truly understand the scientific process. This is your chance to connect the dots and derive meaning. You relate your findings to previous studies or theoretical frameworks. You consider possible societal or practical implications.

Ask yourself: What do my results mean? How do they align with the existing literature – and where do they differ? What can we infer from them?

And yes – you’re allowed to point out uncertainties and limitations. Where might your method have been too narrow? What influencing factors couldn’t you account for? What could have been done differently?

The discussion is not the place for summaries – it’s the place for independent thinking. This is where your thesis starts to become genuinely interesting. Unfortunately, this is also the point where most students stop putting in effort.

One of the most overlooked thesis tips? Make the discussion the heart of your thesis, and you’ll go from borderline pass to top-grade candidate.