You want to conduct a deductive thematic analysis and categorize your qualitative data based on pre-existing theory and concepts?

You’re in the right place.

In this article, I’ll explain in detail and in an easy-to-understand manner how to perform a deductive thematic analysis in 5 simple steps.

What is Thematic Analysis?

To make sure that we are on the same page about thematic analysis, I will mainly refer to the understanding of the method described by Braun and Clarke (2006;2019; 2021).

Please note that there are other authors that have their own idea of thematic analysis, however, the explications by Braun and Clark seem to be most useful to the research community.

It is important to understand that thematic analysis is flexible, which means you can apply it in different variations and customize it for your own needs.

The only thing you need to be aware of is that you do not slap a label on your approach in your methods section and then do something completely different that is not in line with the methodical ideas of the authors you just cited (the “label”).

Flexibility in thematic analysis means that you can combine different approaches such as inductive and deductive coding within the same study. But you don’t have to. It’s up to you and what makes most sense to achieving your research objectives.

In this tutorial, however, I am going to focus on applying thematic analysis in a theory-driven, deductive logic.

If you would like to learn more about inductive thematic analysis, please refer to my previous tutorial about this method.

What is Deductive Thematic Analysis?

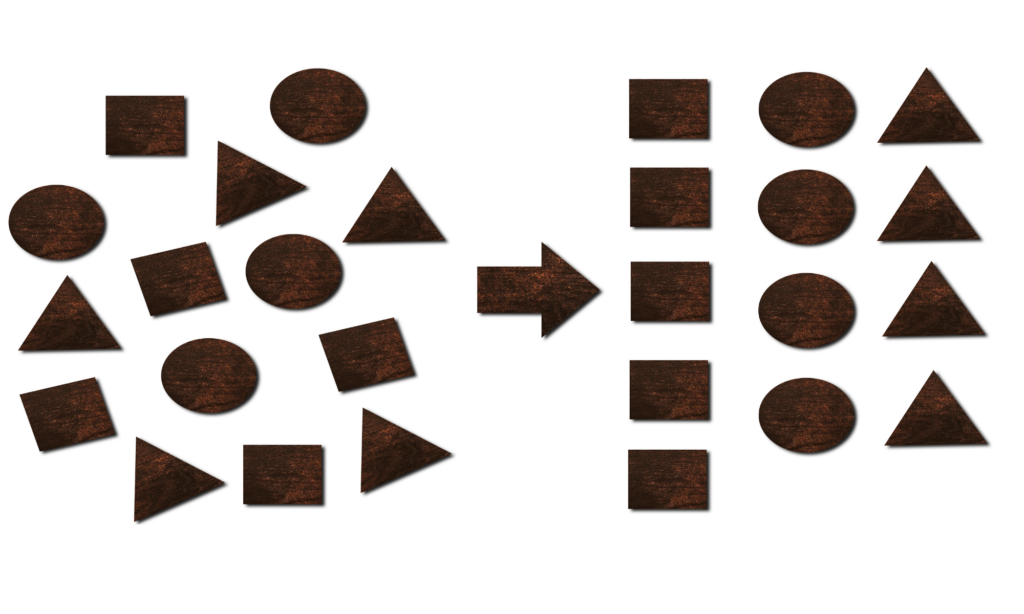

Whereas inductive thematic analysis is data-driven (bottom-up), deductive thematic analysis is theory-driven (top-down).

This means that you do not develop your themes based on the statements you find in your qualitative data (e.g., interview transcripts) or the underlying patterns of meaning of these statements.

Instead, you take these statements, and classify them into a pre-existing theoretical structure.

For deductive thematic analysis, therefore, you need to think about theory before you enter your analysis.

Let’s look at the steps that you need to go through.

#1 Define your Themes

Option 1: Use pre-existing theory

For a research question that involves a specific theory, you should develop your set of pre-defined themes based on that theory. For instance, if the research question is: “What influence does remote work have on organizational identity?”, it references the “Organizational Identity Theory” (Whetten, 2006).

Theories in social sciences are usually based on the work of individual authors who have defined a specific model or the components of a theory. These can be dimensions, variables, or constructs. We take those and make them our pre-defined “themes”.

Themes

Choose the work of an author or team of authors and read the corresponding book or paper thoroughly. In our example, this would be Whetten’s 2006 paper. The author names three dimensions representing organizational identity: the ideational, definitional, and phenomenological dimensions. These dimensions would serve as excellent main themes for your study.

Sub-themes

The original source will provide further details on how these dimensions are defined, which you can use to form subthemes. It may also help to read additional literature that builds on or explains this theory. Often, primary sources are quite complex.

However, you can break down any theory into its components and logically assemble a list of themes and subthemes. A popular approach in thematic analysis is to take the main themes from the theory (in the example: ideational, definitional, and phenomenological aspects of organizational identity) and develop the subthemes inductively, based on the content you find in your data.

Option 2: Derive Themes from the Current State of Research

If your research question does not target a specific theory, such as “How are remote work models implemented in the manufacturing industry?”, you can consult not a single pre-existing theory, but turn to various current studies and extract your themes upfront.

It’s best to work with a table where you create themes and subthemes on the left and note the source(s) from which you derived them on the right.

Examples of categories related to the example could include: “Technological Infrastructure”, “Corporate Culture”, “Work Time Models”, and so on.

It’s essential that these themes clearly emerge from your review of the literature. Don’t worry about overlooking something – you can always expand or adjust your list of themes after an initial analysis round if you notice certain contents are not covered or if you encounter new literature in the meantime.

#2 Create a Codebook

To guide your analysis, you can work with coding guidelines, which are often referred to as a codebook.

Coding in this context simply means classifying a piece of content or statement as part of a theme.

A codebook is particularly useful if you are not the only person coding the data. But it also gives your method more rigour as you systematize your coding process.

Three things are particularly important to consider when you create a codebook for your deductive thematic analysis:

2.1 Define the Themes

Cover this step with the aforementioned table and put it in the document that is supposed to be your codebook.

Add another column where you precisely define when a text segment belongs to a specific category or not.

You can use a concise description of the theme to do so. Make sure to use the references of the particular theory or the literature that you used to derive the theme.

2.2 Use Anchor Examples

For each theme or subtheme, you should insert at least one example in the codebook.

This example represents the respective theme. This could simply be a direct quote from your interviews. If you are analyzing social media content, it would be a tweets, etc.

You might need to do some initial coding until you find a suitable example that you can put in your codebook.

3.3 Define Coding Rules

You can then add further comments that establish the rules how a coder should decide when a data segment is not clearly assignable to a theme.

This ensures that you act consistently throughout the coding process.

#3 Do the Coding

Consider using a software to support your coding such as Nvivo or Taguette.

This helps you to organize your analysis, especially if you have a lot of data.

Option 1: Coding alone

If you are coding alone, you can set some percentages of coding the whole dataset to set aside time for review.

There is no strict rule for this, but I would recommend doing 10% of all the coding and then stop and check if your codebook works.

If not, make changes to it and start over.

The next milstone could be somewhere around 50% of coding all your data.

Check the distribution of data segments that you assigned to your themes and make adjustments to the coding rules if necessary.

Then go ahead and finalize the coding.

Option 2: Coding in a team

If you are coding in a team, the same milestones apply.

However, now you meet as a team and discuss your coding. Compare different examples and check with each other if you are all using the codebook as it was intended.

After you have finalized the coding, you may consider calculating an inter-rater reliability measure such as Cohen’s Kappa.

Here you will get a statistical value that shows how big the agreement is between you and the other coders.

You can only calculate it, if the team members code some portion of the data simultaneously.

For example, you could take 10% of your data and everyone codes it independently. Based on this coding, you calculate the inter-rater reliability and report the value in your methods section.

If the inter-rater reliability is not good, you might have to consider going back to the codebook or redo some of the coding so that you reach better agreement among the team.

#4 Present the Findings

The next challenge is to translate this deductive thematic analysis into a structured and reader-friendly findings section.

I recommend balancing descriptive reporting of the results (e.g., with raw anchor examples (=direct quotes) from your data) and some analytical interpretation (in your own words).

Start with the structure by turning your list of themes into headings. Use subthemes, if you have any, as subheadings.

Then, add the quote examples and explain them in your own words.

Expand these explanations and examples with additional paraphrases that you consider important, and try to explain how the data connects to the pre-defined theme you have derived from literature or theory.

Always support arguments with paraphrases or direct quotes from your data.

Also, make sure to link the subchapters with appropriate transitions.

#5 Discuss Your Findings

What do these findings mean?

Use the discussion section of your paper, report, or thesis to connect back to the theory.

For a deductive thematic analysis, you must discuss your findings in light of the theory or literature you started with.

Writing an outstanding discussion is an art that goes beyond the scope of this tutorial – feel free to check out my tutorial on writing a discussion.

However, consider using tables and figures as additional tools to organize your findings or make it easier for the reader to spot what your most important findings are.

Maybe there were very few data segements assigned to one prticular theme? Or a lot in one?

Discuss what this means in regard to your research question.

If you have specific questions about thematic analysis, leave them in the comments under this video.

If you want me to dive deeper into a particular topic in a separate video, let me know in the comments as well.

Literature

📚 Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

📚 Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597.

📚 Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352.

📚 Whetten, D. A. (2006). Albert and Whetten revisited: Strengthening the concept of organizational identity. Journal of management inquiry, 15(3), 219-234.