Are you looking for a guide on how to write a research proposal for your dissertation or thesis?

You have come to the right place, because in this article, I will show you how to prepare, structure, and write your research proposal in 6 simple steps.

With this knowledge you will easily convince your future supervisor that your research is going to make a difference and you better get the green light to start with it immediately!

What is a research proposal?

A research proposal is a basic outline of a research project. Its purpose is to convey the basic idea of the research that you plan to do and describe the project and its timeline.

In a research proposal, the focus is on the relevance and planning of a project. The goal is to convince the supervisor or journal editor about the potential value of your proposed study.

Ok, tall of this makes sense. But how do you write such a research proposal?

This is what this video is for. In the next 10 minutes or so, you will get a quick and complete solution for writing a research proposal. I have divided the process into 6 simple steps, which you can easily follow through step by step.

Before you start to write you research proposal

You need to know that a research proposal determines the direction of the next weeks and months of your research.

It is, so to speak, the blueprint of your study. Don’t worry if you can’t predict certain things or if you are uncertain. Oftentimes, the final version of how a study turns out differs significantly from the ideas presented in the research proposal.

Nevertheless, utmost concentration is required when writing your research proposal. It is not a tedious formality that must be completed according to the examination regulations.

The more effort you put into your research proposal, the more you will benefit from it during your academic work. This is because you can use all the contents you produce for your you final manuscript as well.

This means that the more effort you put into the research proposal, the less work is left for your final manuscript.

Writing a research proposal not only helps your supervisor evaluate your idea in writing, but also helps you, because it gives you a clear direction and actionable steps to undertake.

Now all we need is a blueprint for the blueprint.

#1 Introduction

The first element of your research proposal is the introduction. Fortunately, you can write it exactly as you would in the final manuscript. There is no difference in the structure of the argument.

You can find a complete guide to writing an introduction on my blog.

The following elements should be included in the introduction of your research proposal:

- Context of the topic

- Research motivation/relevance

- Precise research problem

- Objective(s) of your work/research questions

- Methodological approach

- Expected contribution(s)

With the creation of your research proposal, you already have a nearly complete draft of your final introduction. You can revise it at the end and adapt it to any changes that may come later.

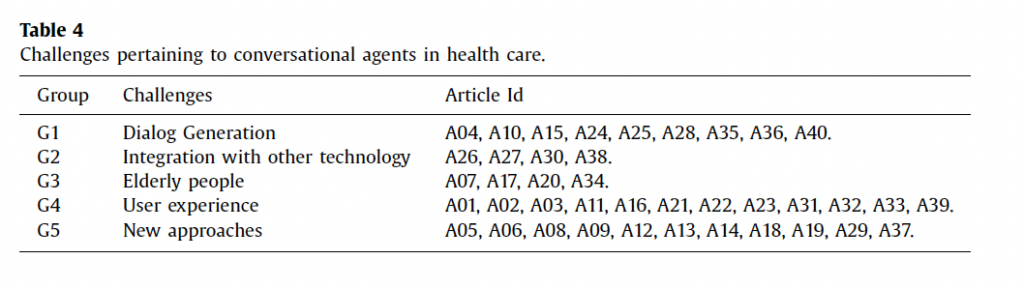

#2 Mini-Literature-Review

You can integrate this part of your research proposal into the introduction (before you propose your research questions) or position it afterwards with its own heading.

Where you place it is not important. The important thing is that you demonstrate that you have conducted an initial literature research.

Focus on current or closely related literature to your topic and clarify the most important terms beforehand.

At the end of your research proposal, you should have a bibliography of about 1 page, which translates to 15 to 20 references.

It’s not enough to have only 3 or 4 references.

#3 Theoretical Framework

If your work is based on a theoretical concept or a specific model, then writing the research proposal is the right time to commit to it.

Explain it in basic terms and possibly include a figure that visualises it. However, do not spend too much time on this part of the research proposal, as it is the part that is most likely to change after you have received feedback from your supervisor.

The amount of effort you put into this should depend on this question: How detailed have you already discussed the theoretical foundation of your work with your supervisor?

#4 The outline of your final project

The preliminary outline is an essential part of writing a research proposal. It serves as a basis for further planning and discussion with your supervisor.

A tutorial about creating a great outline is also linked in the top right corner.

For the outline in your research proposal, it is not enough to simply list the headings of the chapters you plan to write. Add a paragraph to each heading explaining what the section will be about.

This should not happen on a content level – such as in the literature review – but on a descriptive meta-level. Here, you primarily explain your approach for each section to your supervisor.

#5 Timeline

The next step is a bit like project management: you create a timeline by assigning specific milestones with a deadline. This signals to your supervisor that you have thoroughly thought through your work on a planning level as well.

In addition, this timeline provides you with your own guideline for achieving intermediate goals. If you want to delve deeper into the topic, you can make yourself familiar with SMART goal-setting.

To really impress at this point, you can also add your timeline as a graphical representation to your research proposal. You can do this either as a GANTT chart (Free tool: Agantty) or with your own image, which you can put together using PowerPoint, for example.

#6 Bibliography

Don’t forget to create a bibliography at the end of your research proposal. You can have it automatically created by using a reference management program.

Good software includes EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley. Pick whatever you prefer and stick to it. It will save you so much time. Trust me.

FAQs about writing a research proposal

The last part of this tutorial will be a quick answer to the most frequently asked questions about writing a research proposal.

How long should my research proposal be?

The length of your research proposal is usually determined by your department or your supervisor. Typically, 3-5 pages are required. This length should not be exceeded or undershot in order to maintain the character of a research proposal.

Can I reuse content from my research proposal?

Yes. Anything you research or write for your research proposal can be used in the final version of your manuscript.

How much time should I invest in my research proposal?

As much as possible. A research proposal sets the groundwork for everything that comes after. If this groundwork is sound, you can impress your supervisor with a little extra effort and it will be much easier for you to begin with the main project.

What is the difference between a research proposal and an extended abstract?

An extended abstract already includes the results in their basic form and how they can be presented in the context of previous and future research.