Are you trying to overcome your phone addiction but don’t know how?

In this article, I’ll share 7 strategies that have personally helped me keep my smartphone addiction under control.

This way, you can take your productivity to a new level, maintain a genuine connection with the people you love, and finally clear the fog in your mind.

Understand the Root Causes of Your Smartphone Addiction

How often do you look at your smartphone without really knowing why? Whether it’s during a lecture, waiting for the bus, or dining with friends – it seems we can hardly do without it. Just checking the phone quickly? And suddenly, we’re deep in the Instagram spiral or lost in an endless stream of TikTok videos. Why do we do this?

In this article, I’ll show you what’s behind our “smartphone addiction” and how we can be smarter than our smartphones. Are you ready to take back control?

Step 1 towards improvement would be to ask yourself: Why is it so hard for you to put the smartphone aside?

#1 App Development

Behind the scenes, developers know exactly what they are doing. They design apps and social media not only to capture our attention temporarily but to keep us engaged for the long term. Endless feeds that never end and push notifications that keep bringing us back are no coincidence. They are part of a clever strategy to keep us in their apps as long as possible.

#2 Dopamine

On a neurobiological level, this can also be explained. Dopamine plays a key role. This neurotransmitter is released when we receive positive feedback – whether it’s a new message, a like, or another notification. And that’s exactly what keeps us glued to the screen. Imagine your own “Feel-Good Dealer” rewarding you with a sense of happiness. These little reward kicks are like candy for your brain, constantly luring you back to the screen.

#3 Instant Gratification

The phenomenon of instant gratification, a craving for immediate rewards, is another reason why it’s hard to put the smartphone away. Especially in moments of boredom, we automatically reach for the phone. It appears to be the easiest solution to fill that void. However, the instant gratification that smartphones provide can quickly become a habit that is hard to break.

#4 FOMO

Another psychological driver for constant smartphone use is the phenomenon of FOMO. Do you know the feeling? This nagging fear that you might miss out on something if you’re not constantly checking your phone? That’s the “Fear of Missing Out.”

Social networks like Instagram and TikTok amplify this fear by bombarding us with endless updates about the supposedly exciting lives of others. This constant worry about not being up-to-date drives us to compulsively check our smartphones. But the catch is: FOMO is never truly satisfied. Every new video, every new post only confirms that life goes on without us and we might be missing out even more.

# 2 Recognize the Negative Effects of of Your Smartphone Addiction

#1 Desensitization of the Reward System

Dopamine plays a big role. The substance responsible for feelings of happiness. You might wonder what’s bad about that? Well, like many things in life, too much dopamine can be problematic.

If the brain is regularly and abundantly exposed to dopamine, as is the case with constant smartphone use, desensitization can occur. This means that the dopamine receptors in the brain become less sensitive. So, you need stronger or more frequent stimuli to feel the same reward. This can lead to everyday pleasures and interactions becoming less satisfying in the long run.

#2 Increased Stress Levels

Too much dopamine can also lead to a permanent state of stress, as dopamine also affects stress regulation. Your body is then constantly on alert, which can lead to anxiety, sleep problems, and even high blood pressure.

Imagine your brain as an inbox that’s constantly flooded with emails – from messages to games to app updates, the smartphone never stops pinging. It’s no wonder that our brains eventually become overwhelmed and overloaded with stimuli. This information overload can lead to brain fatigue and further increase stress levels.

#3 Impairment of Cognitive Functions

Over time, overstimulation by dopamine can negatively affect your cognitive abilities. If your brain is constantly seeking quick rewards, it can impair your concentration. Studies even show that excessive smartphone use can affect productivity. So, if you ever feel like you’re getting nothing done, banish your phone from the room.

An excess of dopamine can also make you more impulsive and make it harder to control your emotions. This can lead to friction in everyday life and negatively affect your relationships.

And that’s interesting because I’ve often noticed how smartphones change social interactions. For example, when I meet friends and my phone is on the table, I’m much less attentive. It’s a completely different conversation when I leave my smartphone in another room. Although smartphones should theoretically bring us closer together, they often lead to physical and emotional distance between us and our fellow human beings.

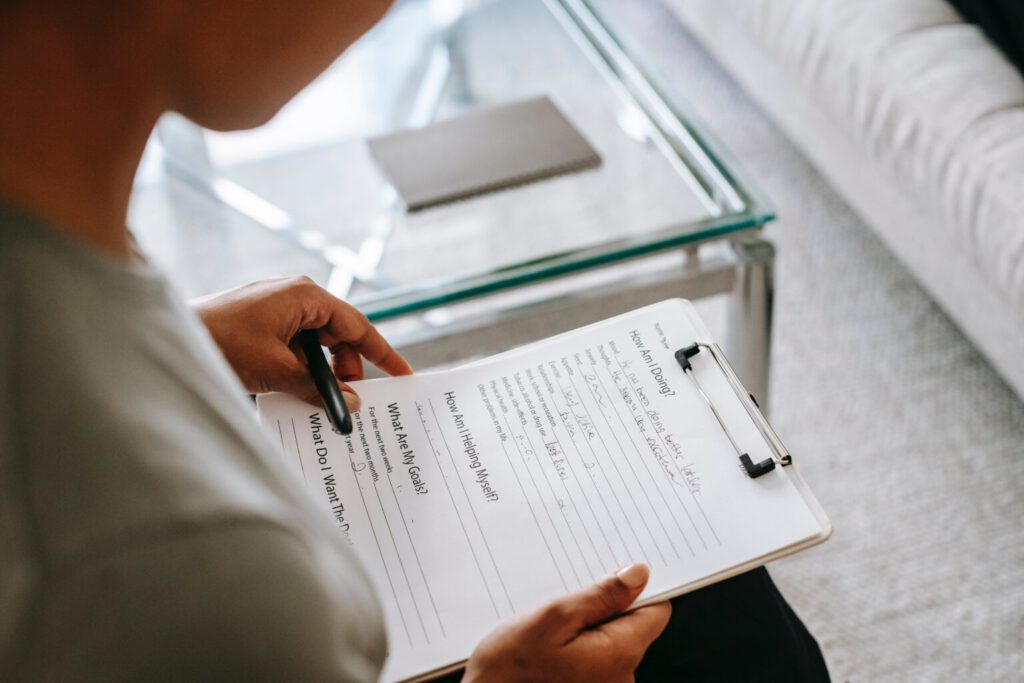

3. Set a Clear Goal to Combat Your Smartphone Addiction

Sure, you could try to completely abstain from digital devices, but realistically, that would be quite limiting. Because, of course, smartphones also have their good sides. They not only keep us connected with friends and family but are also real lifesavers in studies or work. Thanks to emails, calendars, and a flood of apps, our lives remain organized, and we stay informed.

It’s not about banning all digital devices but about making conscious decisions about their use. Who’s in control? Is it your phone, or are you using it as a tool that enriches your life? Ask yourself: What are my values? What do I want to achieve? Does using app XY align with these goals, or is it merely a distraction? By asking such questions, you can ensure that your technology use supports your goals rather than hindering them.

4. Discover Healthier Sources of Dopamine

While smartphones often only provide short moments of happiness (and can have negative effects), there are alternatives that release dopamine more slowly and sustainably – and these are usually much more fulfilling. Here are some suggestions for how you can increase your well-being in the long term and fight smartphone addiction:

Setting and achieving goals:

Setting goals is more than just a good intention. Because each small success releases dopamine, significantly boosting your confidence. Whether you’re rocking your next term paper, achieving a sports goal, or just meditating more regularly – each step towards your goal brings you more inner satisfaction.

Spending time with friends:

Genuine interactions, such as relaxed dinners, spontaneous outings, or deep conversations, are particularly effective at fulfilling your need for human connection.

Learning new skills:

Learning a new skill challenges your brain and expands your perspective. Whether you’re learning a new language, a musical instrument, or knitting – the success of your learning process also releases dopamine. This is a meaningful alternative to the often empty entertainment that constant scrolling on the smartphone offers.

5. Implement a Digital Detox Routine

“Digital Detox” – that is, a conscious break from all digital devices – can be an effective method to reduce overstimulation and improve your mental well-being.

By temporarily abstaining from smartphones, tablets, and computers, you give your brain a chance to recover from the constant stimulus overload. This can improve concentration, enhance sleep, and reduce your stress levels.

A successful digital detox starts with small steps: Perhaps just an evening or a weekend without digital devices. It’s important to use these times consciously to engage in activities that you enjoy and that ground you – whether it’s reading a book, spending time in nature, or just enjoying the quiet.

These digital breaks can help you reflect on your own use of technology and overcome smartphone addiction.

However, digital detox phases, like a day offline or a week without social media, often do not lead to lasting changes. Consider it more of a reset. Although they provide a break, they don’t tackle the underlying habits that lead to our dependency. Without a real change in our daily routines and our attitude towards technology, we quickly fall back into old patterns.

6. Gradually Change Your Daily Habits

Create smartphone-free zones: Decide where and when the smartphone is off-limits. This could be during dinner, on a walk, or at a concert. These moments without a smartphone help you enjoy the experience more intensely.

Monitor your screen time: To reduce our dependency on smartphones, we need to set clear boundaries and make more conscious decisions about when and how we use our devices. Screen time monitoring apps can help you manage your time more consciously.

Restructure your daily routine: Rely on a real alarm clock instead of your phone to wake you up. This way, you’re not tempted to spend the first minutes of your day on the smartphone. Ideally, banish your phone from the bedroom altogether. If you want to know the time during the day, it’s best to rely on a clock.

Regulate your notifications: Turn off unnecessary push notifications and organize your apps into folders. This way, you’re less likely to automatically reach for your smartphone and can decide for yourself when you want to view messages and updates.

Remove distractions: Leave your smartphone in another room when you need to concentrate. This way, you work more productively.

Consciously use breaks: Try not to reach for your smartphone at every opportunity. Use waiting times instead to observe your surroundings or simply think. Such breaks can foster your creativity.

7. Adopt a Critical Perspective on Smartphone Use

Let’s be honest: It’s high time to rethink your relationship with your smartphone. I invite you to take a close look at how and why you use your smartphone and consider if there might be a better way.

Start with small steps and see for yourself how your life and well-being gradually improve. Are you ready to take on this challenge? Because remember – your smartphone should be a tool, not the center of your life.