Have you come across the term “phenomenology” but have no clue what it actually means?

Then this article is just for you.

We’re going to break down mysterious concepts like “transcendental reduction,” “epoché,” and “Intuition of Essences” Sounds like something far removed from empirical science as we know it? Exactly and that’s what makes this topic so fascinating.

But don’t worry, I’ll explain phenomenology in a way that’s easy to understand, showing you how this school of thought and its methodology can be applied beyond dense philosophical texts.

The Philosophy Behind Phenomenology (Husserl)

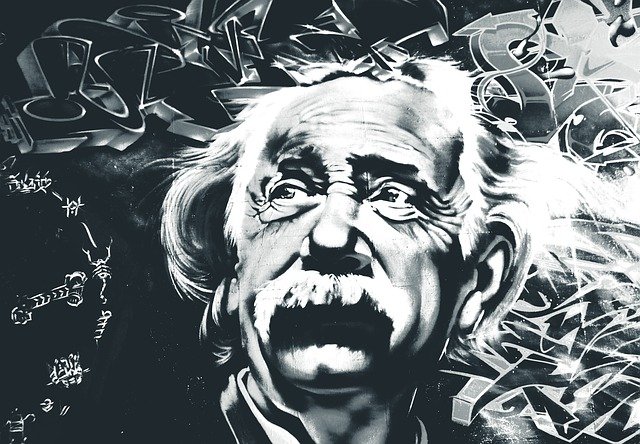

Phenomenology as a philosophical discipline emerged in 1900 with the publication of Logical Investigations by Edmund Husserl, a foundational work that established phenomenology as a distinct methodological approach to studying consciousness. In this work, the philosopher introduced a novel method for examining and exploring consciousness.

What a game-changer!

At the time, psychology was still a young discipline claiming to study consciousness scientifically. To understand why Husserl’s approach was so radical, we need to consider the dominant paradigm of psychology at that time.

Psychology was heavily influenced by positivism – the empirical, numerical study of psychological phenomena modeled after the natural sciences. While this remains the dominant approach in psychology today, it’s far less dogmatic than it was back then.

(If you want to learn more about positivism and how it differs from other epistemological positions, check out my tutorial on ontology, epistemology, and methodology).

Phenomenology fundamentally opposes the positivist mindset, which is why Husserl’s ideas caused such an uproar.

Husserl’s main issue with the prevailing natural science approach was that it entirely ignored the perceiving subject. Yet, things can appear differently to different individuals depending on how their consciousness presents them.

Phenomenology struggled to gain acceptance at first and still holds something of an outsider position today. Nevertheless, Husserl’s work left an indelible mark on the history of philosophy, establishing phenomenology as one of the most significant intellectual movements to originate in Europe.

The Core Idea of Phenomenology

Phenomenology focuses on the phenomenon of consciousness and its various manifestations. The term itself breaks down into “phainomenon” (that which appears) and “logos” (science or study). Phenomenology, therefore, is the science of things as they appear to us.

According to Husserl, the way things appear in our consciousness provides the most powerful basis for acquiring new knowledge.

In other words, the “exact” natural sciences are not the only valid path to discovering new insights. Husserl argued that the human sciences, which approach the world through subjective experience, can also yield valuable knowledge, especially about how we come to understand things.

Phenomenological research should focus on things as they are experienced, free from assumptions and biases. Husserl’s call to suspend biases does not mean that we must completely erase our personal perspective or way of perceiving. Rather, it aims at making us aware of how our preconceptions and assumptions shape our perception and ensuring that we account for these influences in our analysis. Recognizing and reflecting on biases is a crucial part of the phenomenological process.

Husserl identified two key principles for studying consciousness.

(Warning: things are about to get a little mind-bending.)

#1 Consciousness Is Intentional

According to Husserl, every experience in consciousness is directed toward an object. This object could be:

- Real (e.g., the tree outside your window)

- Dead (e.g., Edmund Husserl himself)

- A mental construct (e.g., your idea of Hawaii if you’ve never been there)

That’s already quite a concept to wrap your head around, but it gets even more intriguing:

An intentional act of consciousness can be “full” or “empty.” Imagine waking up in the morning and reaching for your glasses on the bedside table. You know they are there, you need them, and you put them on.

Now imagine you misplaced your glasses the night before. You wake up with the intention of finding them. A disheveled, half-awake person stumbles around the apartment, blindly feeling for objects. An absurd scene, right? But when you understand “empty” intention, the act of searching for an object vividly present in your mind but not in your immediate perception, it suddenly makes perfect sense.

#2 Consciousness Is Separate from Sensory Perception

The second fundamental principle of phenomenology states that sensory perception and conscious experience are distinct. When we feel or see something, we process it in our consciousness—this much is clear. Consciousness functions as the operating system that processes sensory input.

But we can also perceive things in entirely different ways. Imagine you’re in the shower, and out of nowhere, you have a brilliant idea. Where did it come from?

There was no external stimulus or sensory experience that triggered the thought. This means consciousness can be a medium for both sensory and non-sensory experiences.

If we truly want to study consciousness, Husserl argued, we must internalize both of these principles.

The Phenomenological Method

So, how exactly do we study consciousness?

According to Husserl, the process involves three steps:

- Describing the object under investigation

- Applying transcendental and phenomenological reduction

- Gaining an intuitive grasp of essences (Wesensschau)

Before beginning these steps, Husserl insisted that researchers must set aside all prior knowledge that does not stem from direct conscious experience. This process is called “bracketing” or epoché.

#1 Describing the Object of Investigation

The first step involves describing the experience of the object in as much detail as possible from the perspective of the experiencing subject.

In phenomenology, the researcher and the subject of research are often the same person, meaning the philosopher records their own experiences.

When applied in social sciences, phenomenological methods typically use interviews. As a researcher, your goal is to elicit the most detailed description of the subject’s experience.

A good interviewer remains as neutral as possible and encourages the subject to speak freely. For further reading on phenomenological interviews, check out the references linked in the accompanying YouTube video.

#2 Transcendental and Phenomenological Reduction

In this step, the researcher adopts a transcendental attitude, setting aside all empirical knowledge about the object. The focus is solely on the conscious experience. The conditions of this experience are philosophically examined.

For practical applications outside Husserl’s strict philosophical approach, researchers often introduce a compromise. Instead of excluding the external world entirely, they consider the “horizon”—the situational context and external influences shaping the experience.

If someone describes their experience in the metaverse, for example, researchers still acknowledge that it takes place in a virtual environment and interpret the experience accordingly.

#3 Intuition of Essences (Wesensschau)

In the final step, Husserl attempts to determine how the object appears to consciousness. He conducts “imaginative variations,” altering different aspects to see how perception changes. If modifying an element changes the perceived essence, then that element is crucial to the phenomenon.

For contemporary phenomenologists, this step involves analyzing raw data—such as interview descriptions—using inductive logic to identify patterns and commonalities. This approach is related to methods like inductive coding or Grounded Theory.

For precise data analysis steps, refer to existing methodologies. Personally, I recommend Giorgi’s (2017) approach.

Conclusion

As you can see, phenomenology isn’t the simplest concept to grasp. Even if you don’t study philosophy, that’s okay, many struggle to fully grasp Husserl’s ideas.

Don’t be intimidated by Husserl’s complex language and terminology.

If you’re interested in the methodology, which offers an exciting alternative to conventional empirical methods, I recommend starting with secondary literature such as Giorgi et al. (2017) and simply trying it out. Learning by doing!