The Spaced Repetition Study Method is about to change everything you thought you knew about studying.

Do you usually start studying for exams just 5 days in advance? No wonder you forget 80% of the material by exam day.

Educational research suggests that Spaced Repetition is the solution.

By applying this method before your exams, not only will you spend fewer total hours studying, but you can also continue your daily routines totally relaxed in the week leading up to the exam AND expect a top grade.

In this article, I’ll show you how to implement the method in 5 simple steps.

How Does Spaced Repetition Work?

Early 20th-century psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, a pioneer in research on human memory, conducted a series of self-experiments.

He attempted to memorize a series of nonsensical syllables and documented his success.

He found that he forgot information over time if he didn’t repeat it.

This observation led to the development of the forgetting curve, which shows how memories fade if not actively refreshed.

The curve flattens over time, meaning the intervals between repetitions can increase to achieve the same level of recall.

This effect is explained by the multi-store model of memory, suggesting that memories move from short-term to long-term memory.

Spaced Repetition is a study method based on this principle, aiming to anchor information more effectively in long-term memory. The key idea is that you retain information better when repeated over longer periods in increasingly larger intervals, rather than cramming in short, dense intervals.

First repetition: Shortly after initially learning the information. Subsequent repetitions: At increasingly longer intervals.

#1 Understand the Mechanics of the Spaced Repetition Study Method

Imagine retaining everything you study not just for the next exam, but for years. Spaced Repetition makes this possible.

By repeating study material at progressively longer intervals, Spaced Repetition deeply embeds information in your long-term memory, similar to muscle training: regular, well-timed training leads to well-developed muscles.

Just like muscle memory, your brain builds strong recollections for your exams with Spaced Repetition.

Why is Spaced Repetition So Effective?

Each time you recall information after a longer interval, you strengthen the neural connection to that information, akin to turning a path in a dense forest into a broad road. These “roads” in your brain help you quickly retrieve information years later.

Studies support Spaced Repetition’s effectiveness, showing that recalling study material at increasing intervals challenges your brain to retrieve information from deeper memory layers (e.g., Cepeda et al., 2008).

This process of active recall solidifies your knowledge more sustainably than repeating information in short, dense intervals.

To outperform 95% of your peers, start studying with short, semester-spanning sessions as soon as you get the lecture notes, rather than cramming at the last minute.

#2 Your Spaced-Repetition Schedule

Moving on to the foundation of the study method: the schedule.

While the science and principle of Spaced Repetition sound great, without a good plan for its implementation, it’s pretty useless.

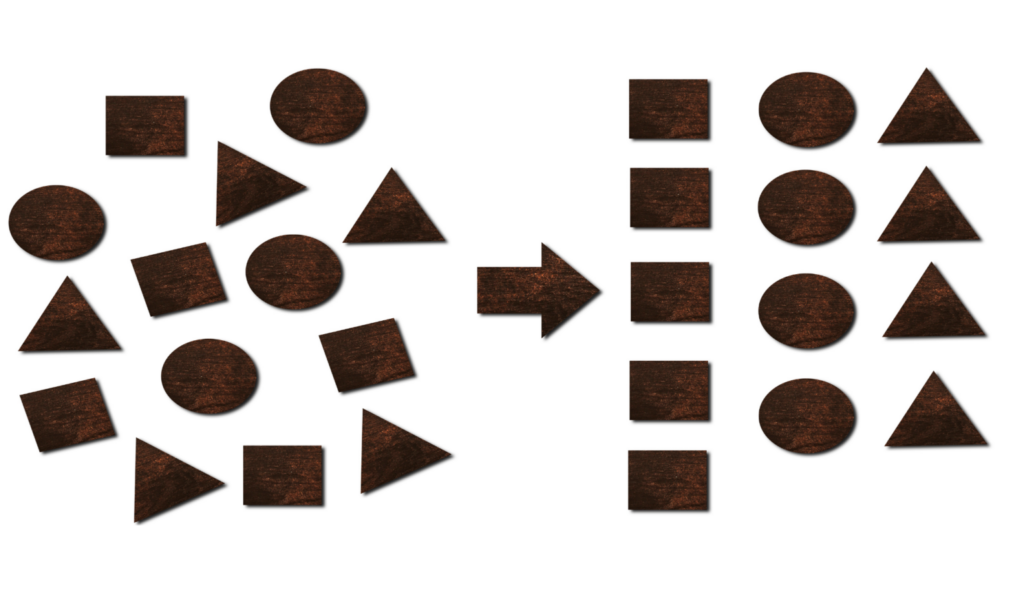

First, get an overview of your study material and break it into manageable parts. Then, distribute these parts over a period leading up to your exam or the end of the semester, starting as early as possible.

The trick: You don’t repeat each part at regular intervals but in increasingly longer ones, e.g., on day one, then after three days, a week, two weeks, and so on. This may sound complex, but don’t worry—there are apps and software to help (more on that soon).

All you need to do is adjust your schedule for various exams so that the more frequent repetitions at the start don’t all cluster in the first week of the semester. Begin with the material for the exam scheduled earliest at the end of the semester.

Now that you have a plan, it’s time to integrate it into your daily life.

Make Spaced Repetition a (nearly) daily habit by finding a fixed time each day, perhaps in the morning or between lectures, and dedicate this time to your Spaced-Repetition study sessions.

Tip: Pair this session with something you enjoy, like your favorite café or an episode of your favorite podcast afterwards. This makes learning less of a chore and more a part of your daily routine you can look forward to.

Example Spaced-Repetition Schedule: Let’s say you want to learn a specific topic for an exam.

Here’s a simple schedule for applying Spaced Repetition:

Day 1: Study the new topic (e.g., Lecture slide deck No. 1)

Understand and process the information thoroughly. Clarify any questions (e.g., in a tutorial).

Day 2: First repetition. Review the previous day’s learning to solidify it. Use flashcards or software.

Day 4: Second repetition. Repeat the topic to strengthen the memory. Day 7: Third repetition.

Day 14: Fourth repetition. Review the topic again.

Day 28: Fifth repetition.

Day 30: Exam.

Maintain these intervals for all sub-topics (e.g., lecture slide deck). If you can stretch the period even further, to 60 or 90 days, even better.

This schedule is just an example and can be adjusted based on individual progress and needs.

The key is increasing the intervals between repetitions, maximizing the method’s effectiveness.

But in our digital world, you don’t have to create your study plan from scratch; there’s software for that.

#3 Software Tools

Traditional flashcards are great for manually implementing Spaced Repetition. Write a question on one side and the answer on the other.

If you answer a card correctly, move it further back in the stack. Incorrect answers go to the front.

Utilize the Active Recall principle at this point.

As we live in the digital age, you don’t have to make things harder for yourself.

There are many tools like Anki, Quizlet, or Memrise that help organize your study material and automatically adjust repetition intervals. These apps use algorithms to determine when you’re ready to revisit specific information.

In a comparative study among 3 groups (1: without Spaced Repetition, 2: Spaced Repetition, 3: Spaced Repetition with algorithmic personalization), the group with algorithmic personalization achieved the best exam results (Lindsey et al., 2014).

An algorithm can analyze how well you remembered information last time and how long ago that was.

Based on this, it calculates the ideal time for the next repetition, meaning the repetition intervals aren’t fixed but dynamically adjust to your study progress.

A major advantage of these apps is personalization. Everyone learns differently, and these tools take that into account.

If you make faster progress on a topic, the repetition intervals extend.

For topics you struggle with more, they shorten. This ensures you use your time efficiently and focus on areas needing more attention.

Many of these apps also offer tracking and gamification features, allowing you to monitor your progress.

This not only provides transparency but also motivation. It’s incredibly satisfying to see your knowledge build over time and how your efforts pay off.

#4 Time Management and Efficiency: Study Smarter, Not Harder

“Spaced Repetition sounds good, but that means I have to start studying in the middle of the semester. That seems quite laborious.”

Ultimately, Spaced Repetition doesn’t necessarily mean investing more time in studying. You’re just distributing your time differently. Instead of cramming for 7 days and nights before the exam, you study continuously throughout the semester for a few hours each week.

Spaced Repetition is a real time-saver.

Rather than spending hours cramming and then forgetting most of it, Spaced Repetition allows you to learn more efficiently. By repeating information at optimal intervals, you spend less time reviewing things you already know and more time on what you need to learn.

This also means you spend less time studying and more time for other important things – whether for other courses, hobbies, or just relaxing.

Spaced Repetition helps you learn more—in less time.

#5 Combine the Spaced Repetition Study Method and Active Recall

If you combine Spaced Repetition with the study method Active Recall, as hinted earlier, you’ll not only reach your goals faster but also with a deeper understanding and longer-lasting memory.

With this approach, your next exam is sure to be a success. I’ve linked a video on Active Recall here for you.

Further Reading:

Cepeda, N. J., Vul, E., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J. T., & Pashler, H. (2008). Spacing effects in learning: A temporal ridgeline of optimal retention. Psychological science, 19(11), 1095-1102.

Lindsey, R. V., Shroyer, J. D., Pashler, H., & Mozer, M. C. (2014). Improving students’ long-term knowledge retention through personalized review. Psychological science, 25(3), 639-647.