Are you already feeling the stress of the exam period at the start of the semester? Has your semester break not been enough to recover from the rigors of the last term?

And do you find it frustrating that despite hours of memorizing and studying, you only managed a mediocre grade?

What do those top students know about study techniques that you don’t?

If this resonates with you, then this article is just what you need. In this article, we will go through the 8 most common mistakes that prevent you from learning any subject and achieving top grades in your studies.

#1 You Start Studying Too Late

We all know that feeling, as the exam approaches, our motivation to study really kicks in – after all, you don’t want to fail.

The pressure is a real motivator to stop procrastinating.

If you’re someone who crams right before the exam and enjoys your free time during the semester instead of sitting in the university library, you’re not alone.

This is how most students study.

However, this method of exam preparation is not really smart and is extremely stressful – this learning strategy is probably the main cause for long nights of cramming and all-nighters.

What if you spread your study hours more evenly throughout the semester?

You don’t need to study more, just more evenly distributed.

Instead of handling the entire study load at the last minute, distribute your sessions evenly over the time you have available.

This means starting early in the semester and regularly reserving time for studying. This way, you won’t panic as exams approach, because you have already laid a solid foundation.

One of the main advantages of this approach is that the number of study hours you invest throughout the semester remains consistent.

You don’t have to catch up last minute on what you typically would have missed until then. This not only leads to a deeper understanding of the material but also makes it easier to remember it.

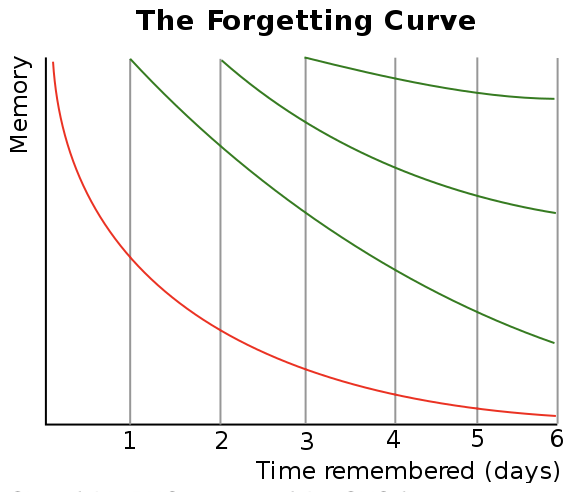

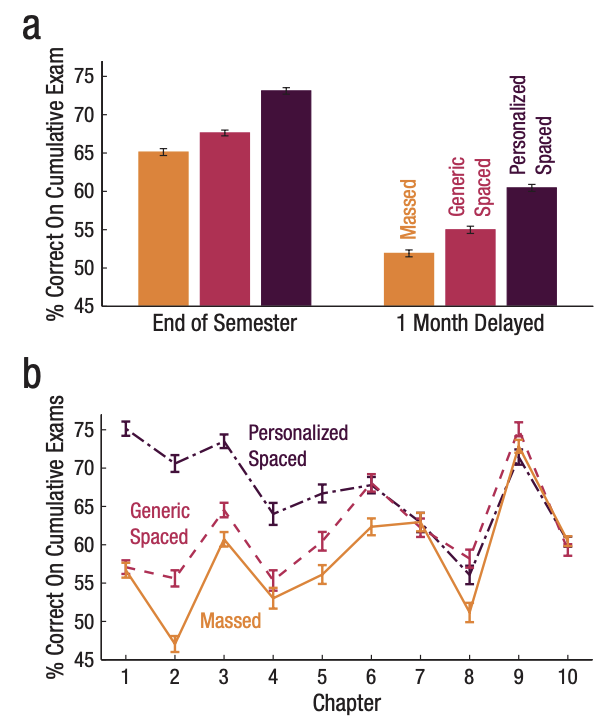

This is also why the Spaced Repetition technique is so effective.

Determine at the beginning of the semester how many hours per day or per week you want to study and then stick to your spaced repetition schedule until the end.

Instead of fear and panic, you’ll walk into the exam with confidence.

So set yourself a goal. For some, it may be 2 hours of study a day, for others, 5. Everyone learns at a different pace. Don’t compare yourself to others. Stay true to yourself.

If you can’t imagine this strategy paying off for you, challenge yourself.

Maybe start this type of exam preparation with just one exam. After that, you’ll see whether you ever want to prepare differently again. 😉

By the way, the Spaced Repetition technique has been around for a while.

It was described as early as 1932 in the book “The Psychology of Study” by C.A. Mace and has since been found to be maximally effective in countless scientific studies.

This approach is a fundamental part of learning how to learn, as it allows for better distribution of study time and long-term memory.

#2 You Study Non-Stop

If you want to takt the learning how to learn thing serious, it’s vital to incorporate regular breaks.

To understand how important this is, think of studying similar to muscle training in the gym.

When you activate neurons and absorb new information while studying, it’s akin to your muscles being exerted during exercise.

Just as your muscles need rest periods after intense exercise to grow and recover, your brain cells also need breaks to consolidate what you’ve learned.

Studies in neuroscience and psychology have confirmed a relationship between learning and breaks and even naps.

Groups of learners who incorporated regular breaks into their study routine achieved better learning outcomes than control groups that did not take breaks.

This means that the brain has the opportunity to process and organize the absorbed information during these breaks.

If you only start studying a week before the exam, you probably have little time to take breaks.

After all, you have to cram all the material into your brain. So this gives you another reason to start right at the beginning of the semester.

Okay, but how exactly should you study now? To find the ideal learning strategy, it’s important to take a look at Bloom’s Taxonomy.

#3 You’re Not Familiar with Bloom’s Taxonomy

This framework elevates your learning how to learn strategy from simple memorization to higher-order thinking skills.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a classification system for learning objectives, developed in 1956 by Benjamin Bloom.

It differentiates various levels of learning. In the lower levels, it’s about the learner being able to remember and understand basic course concepts.

However, the tasks of an exam or assignment are often on the higher levels of the taxonomy, where you are asked to apply, analyze, evaluate, or create new concepts.

To achieve this, you must really process information, not just memorize it. Always check during your study whether you have understood the material on a deep level.

For example, you can summarize concepts in your own words and then apply this knowledge by actively solving practice problems of varying difficulty.

These tasks should test your ability to analyze and evaluate information. When studying, ask yourself at which level you are.

- Can you solve problems?

- Are you able to critically evaluate information, compare concepts, and derive recommendations for action?

For instance, if you’re studying medicine and learn new things about the workings of the heart, you shouldn’t just limit yourself to memorizing medical facts like the function of heart valves.

Instead, you should go a step further and ask yourself how heart valve defects manifest and why they occur.

To reach the top of the pyramid and truly master a subject, teaching others and creating your own teaching materials is one of the best methods.

In doing so, you force yourself to go through the entire taxonomy, develop your own opinions, and teach others based on your own understanding.

#4 Learning How to Learn: You Don’t Enjoy the Process

Learning is supposed to be fun? Yeah, great phrase, but not really possible in reality.

Wrong!

Try to see it differently. For me, learning used to automatically mean memorizing, which I found terribly monotonous and boring.

So, one day I decided, I didn’t just want to learn economics, I wanted to really understand it.

Instead of plowing through textbooks and lecture scripts, I approached it differently.

I first familiarized myself with the subject. And that’s super easy with entertaining content on YouTube, documentaries, or podcasts.

I could hardly believe it myself, but documentaries like Inside Job, Money Never Sleeps, or the books by Ray Dalio for example not only made the subject more accessible but genuinely sparked my interest.

This new approach turned learning into an exciting adventure rather than a tedious obligation.

So, learning can indeed be fun if you find the right ways to make it engaging. And who knows, maybe you too will find an entertaining way to delve into your study topics.

#5 You Only Focus on Your Favourite Topics

Naturally, we prefer to engage with things we are already good at. It’s easier to learn new things in these areas, as it requires less effort. And of course, we prefer the easy path over climbing the mountain.

And besides, learning should be fun, as I just told you.

But unfortunately, you also have to pass subjects that are not your strong suit. To finish with good grades, you have to invest time. So challenge yourself and turn your weakness into your strength.

Believe me, economics was not my favorite subject.

I even disliked it, so I tried to make it easier for myself to access the subject. Try it out, and you might find that the topic isn’t as terribly boring as you thought – sometimes it’s really the boring professor. 😉

Challenging yourself to study less-preferred subjects is crucial for learning to learn.

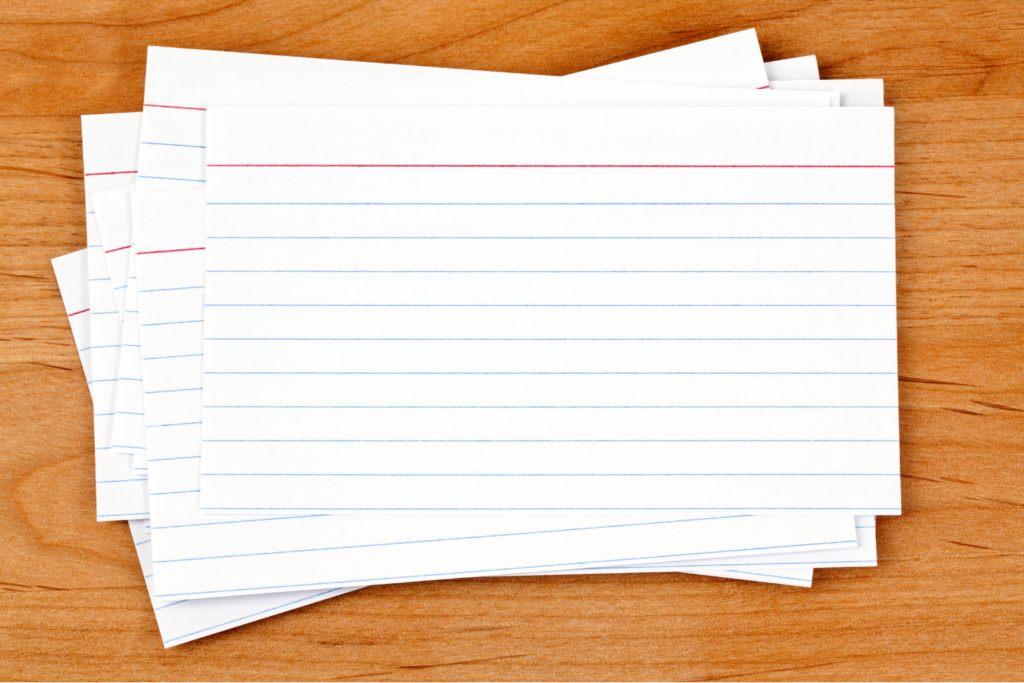

#6 You Study with Flashcards

My beloved flashcards, that’s how I always used to study!

Nearly all of my fellow students also had a stack of 268 flashcards on the table in the library. Why should that be a mistake?

Let me explain.

On one side of a flashcard is the question, and on the other is the answer.

And what is the goal of flashcards?

Memorization.

And if we recall Bloom’s Taxonomy, memorization is at the lowest level. So, you are most likely not going to get an A+ in the exam using them.

Flashcards are not optimal because they focus on isolated facts and not on the overall context. Yet, it is this context that is important for comparing information, showing contrasts, and applying learned material to new situations.

These tasks are higher up on Bloom’s Taxonomy and secure you the top grade.

Move beyond flashcards and embrace Active Recall as a powerful tool in your learning how to learn arsenal.

- You read a part of the material and then put it away.

- Then write down everything you remember and phrase it in your own words.

- Then read the text again and check which information you missed.

Repeat this process until you know everything.

#7 Focusing on Memorization

I’ve already hinted at it, but this point is so important that I can’t stress about it enough.

In most cases, you can actually completely save yourself from memorization techniques, apart from a few exceptions like the first semesters of a medical degree, for example.

If you start solving problems and achieve a deep understanding of the material, you’ll not only understand connections better but will also automatically remember the facts over time.

Even though it seems counterintuitive at first, if you focus on memorization, you will forget information faster than if you build relationships between facts. This way, the learned material goes not only into your short-term but also your long-term memory.

So, in exam preparation, focus on tasks that are at the application, analysis, and evaluation levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

This means you shouldn’t just passively read your notes and books. Engage with the material and don’t just highlight text in color.

Really think about what you read. Answer questions that arise while reading and research information that goes beyond the script.

#8 You Study Without Using Mock Exams

Incorporate previous or mock exams into your learning how to learn journey. Right at the beginning of the semester, you should download past exams.

Old exams provide insight into the format and style of the exams. This can help you better prepare for the specific requirements of the test.

Also, you see which topics or types of questions were more common in previous exams. This allows you to focus your preparation on the areas that are likely to be tested.

By solving old exams, you can improve your time management for the test. You can find out how much time you need for different tasks and how to divide them most efficiently.

Furthermore, by going through the old exams, you can identify your knowledge gaps and weaknesses and focus your revision on exactly these areas.

But here’s another important reminder. Don’t just memorize the answers to the old exams. It is very unlikely that the same questions will be asked again. Therefore, focus on a deep understanding and application of your knowledge.